Home | Articles | Search | Enroll | Equipment | Mello Chest | Souvies | Links | Updates

Early Bugle Usage in the New World

Prior to the American Revolution (1775-83), Colonial Volunteer Militia Cavalry Units were organized by the individual colonies. These ranks were filled with able-bodied men between eighteen and forty-five years of age. Musicians were included in these ranks and were sometimes freed slaves that were not permitted to “bear” arms. Finances permitting, natural trumpets (sometimes with decorative tabards) were utilized as signaling instruments. The presence of trumpeters in early American militias is confirmed by existing muster rolls.(23)

|

|

|

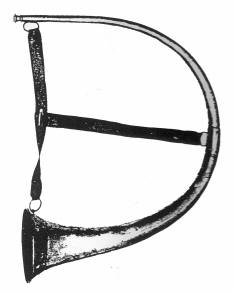

Hanoverian Bugle horn (eighteenth century). From New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. |

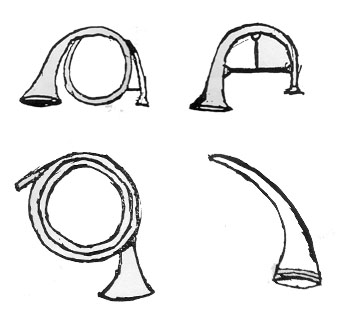

Foreign forces occupying North America during the American Revolution introduced bugle horns to Colonial America. One of the bugle horn types of this period is nearly identical to the hunting horn and the natural horn. However, the bugle horn could be found in other shapes. The Prussian bugle horn, later adopted by the Electorate of Hanover and sometimes referred to as the “Hanoverian bugle horn,” is a half-moon-shaped instrument pitched in “C.”(24) Other types of bugle horns are pictured in powder horn engravings and include numerous configurations.(25)

One of the first uses of the bugle horn on American soil was documented in Camus’ Military Music of the American Revolution: “At the battle of Harlem Heights, the Americans met some of the British light infantry and the Hessian jäger [soldiers]. These riflemen were special companies of hunters, uniformed in green, and serving as light infantry. At the beginning of the battle, as General Washington’s adjutant Joseph Reed described it, ‘The enemy appeared in open view, and sounded their bugles in a most insulting manner, as is usual after a fox chase. I never felt such a sensation before—it seemed to crown our disgrace.’”(26)

|

|

|

|

Powder horn engravings representing various styles of bugle horns. From Military Historian and Collector, Spring 1984. |

The British utilized bugle horns instead of cumbersome drums for its newly formed light infantry units. Some musicians were required to perform on fife, bugle horn, and trumpet. Trumpets were used for mounted troops, bugle horns or fifes and drum for dismounted dragoons serving as infantry.(27)

bugle horns became associated with the enemy by Continental troops and were, by default immediately disliked. Combined with shortages of brass instruments available to the troops, improvisation had to occur to locate effective signaling instruments. This can best be demonstrated by Daniel Morgan’s use of a turkey call as a signal to rally his Corps of Riflemen at the Battle of Saratoga in 1777.(28)

Despite the bugle horn’s association with the enemy, some Continental Cavalry unites favored trumpets and bugle horns during the Revolutionary War. There’s also evidence that at least two ships in the Continental Navy used bugle horns along with trumpets during this time.

By 1778, the Journals of the Continental Congress listed musicians used by the military in the following configurations:

|

Configuration of Musicians used by the Continental Army as of 1778 |

|

|

Infantry Battalion |

1 Drum major, 1 Fife major, 18 drums and fifes |

|

Artillery Battalion |

1 Drum major, 1 Fife major, 24 drums and fifes |

|

Cavalry Battalion |

1 Trumpet major, 6 Trumpeters |

|

Provost |

2 Trumpeters (29) |

The number of musicians utilized by the military remained virtually unchanged until 1941.(30) After 1875, bugles were used in lieu of fifes until drummers were also discounted.(31)

The Bugle Horn becomes the Bugle

Toward the end of the eighteenth century, a dramatic change occurred to the shape of the bugle horn when the instrument was coiled in a fashion similar to the trumpet. Other than it’s shape, the instrument remained virtually unchanged.

The discovery of an exact date that the coiled bugle was first utilized has proven inconclusive. However, specimens of this configuration were manufactured as early as 1800. The British military has been credited for initiating copper bugles of this design and it formally adopted the patter in 1812.

During the late eighteenth century, drill manuals throughout Europe were being appended to include standardized signals for buglers. The Prussian cavalry received standard signals no later than 1787. French trumpeter Joseph David Buhl spent decades revising traditional French military signals.(32) Many of these signal were incorporated by other countries. At least ten calls utilized by the U.S. Army were created by Buhl and are still in use today, including: “First Call,” “Mess Call,” “Retreat,” and “Tattoo, First Strain.”(33)

The War of 1812

Bugles of this time period were available in many shapes and sizes. Typical shapes included coiled, half-moon, and the elongated coil similar to the trumpet. Regardless the shape, the bugle filled an important strategic role in the War of 1812 (1812-1815).

|

|

Bugle in C by British instrument maker Thomas Key circa 1811. From metmuseum.org. |

On at least two occasions, British forces in Canada utilized the bugle in a manner that transcended simple signaling. On October 26,1813, Lieutenant Colonel Charles De Salaberry (who learned of bugle horn methods as an aide for Major General Francis de Rottenburg's 60th Rifles of the British Military(33a)) distributed his buglers during the battle of Cateaugay to sound calls from the woods. The advance signaled from the woods was heard by the Americans, who retreated when it was assumed that a charge was forthcoming. However, De Salaberry did not have sufficient troops for a successful advance and sent his buglers out to “fool” his adversaries—which he did. A similar tactic was utilized at the battle of Longwoods on March 4, 1814. Buglers were posted in three different directions as they signaled commands. The purpose was to mask the actual direction of the British assault.(34)

The U.S. Army had only one regiment permitted to use the bugle instead of the fife and drum during the war, besides self-governing militias. The U.S. Rifle Regiment utilized the bugle, and the instrument soon became associated with the riflemen. It’s unclear what styles of bugle the riflemen used. Uniform insignias at the time describe two types of bugle horns.(35)

In 1814, the Rifle Regiment was expanded to four regiments, each utilizing the bugle. However, the 1st Rifle Regiment utilized a field trumpet on at least one recruitment drive on August 19, 1814. This “trumpet” could have been a true cylindrical field trumpet, or a folded trumpet-shaped conical bugle that was erroneously identified.(36)

During the war, the bugle found its way into several major U.S. military music ensembles. The United States Marine Corps Band ordered a bugle of “trumpet kind” in 1812.(37) Keyed Bugles (discussed below) were incorporated into the Army Band at the West Point Military Academy.(38)

American Fife, Drum and Bugle Corps

During 1828, military fife, drum and bugle corps comprising of reed and brass instruments, as well as fife and drum corps, were utilized by the American military. Ned Lothian originated the practice of having brass bands alternate with fife and drum corps in playing different quick steps while on the march. At the time, these “brass bands” were comprised of natural trumpets and horns.(39)

As the keyed bugle came into vogue in the United States, it was also incorporated in fife, drum and bugle corps along with cavalry trumpets. Since the keyed bugle was a chromatic instrument, it would often alternate the moldy with the fifes.(40)

|

|

|

A French "Church" style serpent (used from 1590 through the 1830s) that saw usage in early brass bands. |

Throughout the 1820s and 1830s, hybridized drum, fife and bugle corps existed in the United States. However, the era of these ensembles was to be short-lived. During the 1830s, “brass bands” could consist of keyed bugles, natural horns, slide trombones, and serpents. This latter instrument was a bass instrument made of wood and covered in leather. The serpent had its pitch manipulated with finger holes instead of valves. These early “brass bands” began to replace the fife, drum and bugle corps and sparked the explosion of brass band music in the United States.(41)

Fife, drum and bugle corps may have been endangered during the ear of the brass bands, but they were in no way extinct. Examples of martial music from the 1930s for civilian drum corps have section set aside for fifes. Instructions were provided in the music for buglers to extend their slides in order to drop their bugle into the key of “F” when fifes were used in the ensemble. If fifes were not used, performers were instructed to omit portions of each musical selection designated for fifes.(42)

|

|

|

Old Guard buglers utilizing valveless coiled copper bugles in a performance during the 1970s. |

The Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps stationed at Fort Myer in Virginia is a very well known modern fife, drum and bugle corps. This esteemed military performance ensemble has incorporated specialty bugles, including a set by the R. Lawler Company of Orlando, Florida in the early 1990s. These copper instruments were designed in the mid-nineteenth century style, but with a modern horizontally positioned piston valve.(43) Ironically, the valve placement is designed to hide the presence of the valve from the casual observer. This mimics the design utilized by the American bugle manufacturers when the horizontal “hidden” piston valve was incorporated in the 1930s.

|

|

|

|

Sandra Quaschnick, right, and J.B. Greear, perform as part of the Old Guard Fife and Drum Unit in Cherry Lane Park on July 28, 2005. Note the hidden horizontal piston actuated by the players' right thumb. These horns are believed to have been fabricated by Kanstul Musical Instruments. Kate Lattanzio photo. |

Keys versus Valves

During the 1800s, a marked advancement in brass instrumentation usage and design occurred. This instrument design “rush” was prompted by improved manufacturing techniques, but was also fueled by the increased melodic requirements of the music of the period. As a result, countless variations of padded key assemblies, rotor valves, and piston valves were devised for brass instruments. Entire families of brass instruments were now able to enjoy the benefits of being fully chromatic.

As early as the fifteenth century, Leonardo da Vinci had conceptualized a chromatic trumpet that utilized tone holes. Slides were eventually used on trumpets to enable the instrument to transcend the limitations of the overtone series. The resulting chromatic instrument eventually evolved into the present-day trombone. Padded keys were utilized on trumpets near the end of the eighteenth century. Several famous musical works for trumpet that remain popular today were specifically created for soloists utilizing the keyed trumpet including Haydn’s “Trumpet Concerto in E-Flat” (1796) and Hummel’s “Trumpet Concerto in E-Flat” (1804). Despite early success, the placement of the keys on the trumpet made it awkward to play. When instrument designers first saw the coiled conical bugle, they envisioned an instrument whose design would permit easily accessible keys.

|

|

|

|

Keyed trumpet by Carl August Müller circa 1830. Photo by Janos |

The creation of a chromatic bugle was realized in 1810 when Bandmaster Joseph Haliday created the keyed bugle, also referred to as the “Kent bugle.”(44) This instrument design evolved into various voices and became popular among British bands in the early 1800s. Despite its success and the presence of exceptional virtuosi, the keyed bugle had to compete with new refinements in valved brass instrumentation beginning in the 1830s. Not recognized as a military signaling instrument, the keyed bugle enjoyed immense popularity in the United States as a commercial solo instrument.

|

|

|

Keyed bugle in B-flat (1835–36). John Augustus Köhler, English, 1805–1878. From the Museum of Fine Arts (Boston). |

European instrument designers began competing with each other for awards and patents that inevitably led to lucrative military contracts. Fierce rivalries occurred between Adolph Sax and many other prominent French manufacturers. The resulting competition that occurred between these manufacturers of valved instruments prompted a startling proliferation of new instrument designs.

It wasn’t long before the larger manufacturers of valved instruments were out producing the keyed bugle manufactures. Soon these valved instrument manufacturers began somewhat of a smear campaign against the keyed bugle as popular bugle soloists were enticed to switch over to valved cornets. However, many music enthusiasts preferred the variety of tone qualities in keyed brass ensembles as opposed to the analogous sound of the similarly fashioned valved brass instruments. Most valved brass instruments were replacing keyed brass instruments by the time of the Civil War (1861-1865), but keyed bugles could occasionally be found in brass bands throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century.(45)

The Royal Artillery Bugle Band

|

|

|

Bandmaster James Lawson (1826-1903) was noted for his role in developing one of the first fully chromatic bugle bands. Photo from britishempire.co.uk. |

The 1850s represent a very crucial time in the era of the chromatic bugle. No group had more of an impact on the evolution of the bugle than the Royal Artillery Bugle Band. Located in Woolwich, England, the ensemble started as a drum and fife band in 1748. Following the Crimean War (1853-1856), the existing drum and fife band was turned into a bugle band. The Fife-major James Lawson became the bugle-major of the ensemble and quickly began training twenty-four “youthful buglers” outfitted with British service pattern bugles.

Lawson devised colorful musical arrangements for his ensembles and occasionally divided the music into two and three parts—no easy task considering the five-note capability of the bugles used. The limited range of the bugles frustrated Lawson to the point that he conceived Henry Distin to allow him to use a chromatic attachment for the bugle patented by Distin in 1855. This attachment provided the bugle with the same chromatic capabilities of the cornet.

|

|

| Musicians uniforms of the Royal Artillery Bugle Band circa 1880s. From britishempire.co.uk. |

With the chromatic restraints lifted from his bugle band, Lawson began to enrich his musical arrangements. The performance by his bugle band of the Roast Beef of Old England, as the “Officer’s Mess Call,” created “quite a furore.” (47) The interest was sufficient enough in the “Chromatic Bugle Band” that hundreds gathered each evening to hear the ensemble perform the “Tattoo.”(48) The bugle band of this period grew to include three voices of copper bugles by Distin (2 “E-flat” sopranos, 18 “B-flat” bugles, 4 “E-flat” tenor bugles).

Further refinements occurred to the bugle band when Distin prepared a bugle utilizing a type of transposition valve. Manufactured in 1861, the instrument was similar to a conical British duty bugle, but with a type of rotary valve.(49) The rotary valve allowed access to cylindrical tubing that lowered the pitch of the instrument from “E-flat” to “B-flat.” The result was a “duplex” instrument that served bugling duties in keys suitable for cavalry and infantry. In effect, this is among the first examples of the piston bugle that would be utilized by competing drum and bugle corps in the United States beginning in the 1920s.

|

|

| A duplex bugle from the late nineteenth century. This instrument is pitched in "C" with a switch valve that lowers the pitch one full-step to "B-flat." From the collection of Jeff Mitchell. |

It’s interesting to note that the Distin bugle manufactured in 1861 was not adopted by the War Office. Even though the instrument would have allowed its field buglers to carry one instrument instead of two, the War Office objected to the dark timber of the “E-flat” side of the instrument. The duplex bugle was not accepted by the English, but a variation of the instrument found favor with the Spanish military at the end of the nineteenth century.

During the early 1860s, Lawson began introducing brass band instruments into his bugle band. By 1869, the group was officially renamed the Artillery Brass Band.

Pelitti and the Bersaglieri Horn

Guiseppe Clemente Pelitti of Italy produced a bugle in 1830 that was immediately adopted by the Austrian Army and the Ottoman Empire. Soon afterwards, Pelitti further refined the instrument we now know as the euphonium and produced entire families of similarly shaped brass instruments. In 1847, Pelitti’s experimentation resulted in the first duplex prototypes.(50)

Duplex instrumentation of the time usually consisted of a brass instrument with two separate bodies and bells connected by a switch valve. The performer could continue playing the instrument in a different key by engaging the switch valve. This concept is still utilized in today’s orchestral “double” and “triple” horns. Adolph Sax realized the potential of such a novelty. Upon viewing prototypes, Sax traveled to Paris for the 1855 Exposition, promptly stole the idea from Pelitti from his entries into the competition. Sax had instruments utilizing Pelitti’s design concepts fabricated immediately and entered into the same exposition, winning first place!(51)

|

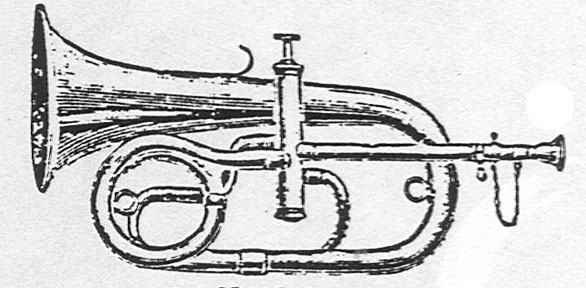

| Infantry Bugle in C with piston valve from a C. Bruno Catalog dated 1888. This instrument is designed in a style very similar to the instruments created by Pelitti for the Italian Bersagliera. |

|

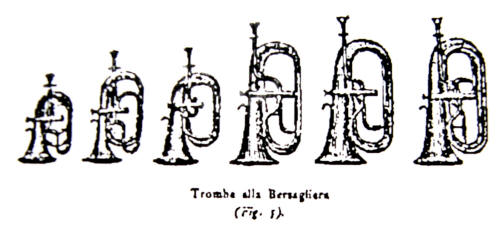

| Tromba alla Bersagliera circa 1871 fabricated in multiple keys and voices as produced by Pelitti (from the Historic Brass Journal). These instruments indirectly impacted the drum and bugle corps in North America that would gain popularity beginning in the 1920s. |

Pelitti died in 1865, leaving his factory to his son (also named Guissepe). An artful entrepreneur, Pelitti produced families of similarly proportioned conical bored brass instruments that quickly gained favor amount mounted military bands.(52)

Shortly before 1870, Pelitti invented the famous tromba alla bersagliera, also know as the “Bersag horn.” This was a family of seven bell-front brass instruments pitched in “B-flat” and “E-flat.” Each voice of the “fanfara” (or bugle band) had a single vertical piston valve that lowered the instrument’s pitch by a fourth. Clever voicing of these instruments enabled the “choir” to collective produce a diatonic scale that offered more musical variety compared to the limited overtone series of simple bugles and cavalry trumpets. The bass horns incorporated into the fanfara had the duty of providing the tempo because percussion instruments were not used by the Bersaglieri.(53)

|

|

| The modern tromba alla bersagliera performing in Italy. Click here for a video of a typical Bersaglieri performance. |

The Bersaglieri were sharpshooters. Famous for their shiny black hats with tufts of cock feathers, they were more properly distinguished by their rapid marching style. Their double march could easily cover a mile in nine minutes.(54) The Bersaglieri’s practice of entering battles with a flourish of brass music made the units popular among American troops during the First World War (1914-1918).

The Bersaglieri’s style and instruments clearly impacted the direction of drum corps in the United States. Single valved bugles in the U.S. are sometimes still referred to as “Bersag horns” because of their close alliance with the tromba alla bersagliera.

There’s evidence that C. Bruno & Son, an instrument importer based in New York, offered single piston “C” bugles of the Bersag style as early as 1888.

The Bersaglieri continue their “quick-moving” style of brass music to this day. Presently, they use modern three-valve version of the famous Bersag horn.

Bugle’s Use in the American Civil War

|

|

| Union soldier is presented with his Clarion in this Carte de Vista circa 1863. |

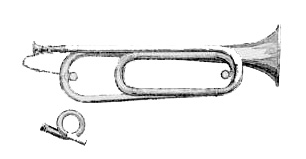

The first known regulation or “pattern” bugle incorporated by the U.S. military appeared around 1835. This instrument was designed in a French style and had a large single coil copper bugle in the key of “C.” By 1861, there were three basic regulation patterns specified for trumpets and bugles, a large “C” bugle with our without “B-flat” tuning crook, a “G” trumpet and an “F” trumpet. Many variations of these instruments were also present.

French military influence on the U.S. military during the Civil War (1861-1865) prompted the substitution of the bugle in fife and drum corps by some volunteer units. U.S. bugle corps resembled French corps very closely. Many of the bugle signals used during the war even came from the French military. There were usually one or two buglers per infantry battalion to sound the skirmish calls, while cavalry and artillery had the normal two buglers per company or troop.

|

|

|

|

Colored lithograph [Detail] from "Zouave Grand Parade March," Duett for Four Hands, composed by S.D.S. (Philadelphia: Lee & Walker, 1861). Music Division. |

John F. Stratton established a musical instrument factory in New York in 1860, just in time to benefit from government orders for instruments. Stratton manufactured more than sixty thousand field trumpets and bugles for the government during the Civil War. His facility’s workforce (averaging between one hundred and fifty to two hundred men) produced an impressive total of one hundred instruments per day!(55)

A few volunteer infantry units, including the brightly-attired “Zouaves” used bugles in lieu of fifes. American Zouaves wore uniforms patterned after the French Light Infantry Zouaves that were formed originally from the Zouaoua Tribe of Berbers in Africa.(56) Combined with drums, the resulting ensembles were some of the first true drum and bugle corps in America. Bugle marches for these ensembles can be seen in at least one music manual from the Civil War.

The Demise of the Fife in Army and Marine Corps

Brass bands had managed to obtain a strong foothold in American society during the second half of the nineteenth century. Bugles were still used primarily for signaling purposes during the Civil War and martial music was being performed by regimental bands and volunteer musicians.

The United States Army and Marine Corps discontinued its use of the fife for signaling and adopted the bugle around 1875. Changes in military tactics in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) created extended lines of troops in the field instead of closed ranks and files. The bugle was more effective than the human voice at transmitting commands along the long lines of troops.(57)

The fifers of the U.S. Marine Corps were note pleased with the adoption of the bugle in place of their fifes. Matters turned worse when a school was established at the Marine Barracks in Washington, D.C. for the purpose of training them to play bugles. Protests occurred, but the fifers were informed that they would not be allowed to enlist unless they agreed, in writing, to learn to “blow the bugle.”(58) Nonetheless, fife music remained part of Army music manuals and Quartermaster’s catalogs listed the availability of fifes through World War II (1939-1945). Despite the fact that they were not used as signaling instruments, fifes never quite disappeared from military service.(59)

The Queen’s Own Bugles

Organized in 1860, the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada was a rifle regiment that utilized one or more buglers as signalers. Eventually a small “band” of bugles were lead by Bugle-Major Francis Clark. Comprised solely of buglers from each of the regiment’s companies, this ensemble did not utilize percussion.

The concept of a bugle band was secondary to the musician’s role as signalers for their respective companies, but a performance ensemble was evolving as bass drums were added to the band in 1866.

Following the death of Francis Clark in 1876, Charles Swift took over the band. Swift, new to the ensemble was noted for his talent on the drum and bugle. Confirmed as Bugle-Major in 1880, he had molded the bugle band into one of the finest marching ensembles in the British Empire:

Swift could produce a richness of tone in the horns perfectly complimented by the flams, drags and strokes of the drums. Drill with the horns and drum sticks reached the same perfection as the foot drill.(60)

In addition to his ability of increasing his ensemble’s precision, several innovations were introduced by Swift into the bugle band. Most notably would be his introduction of crook adjustments for a portion of his bugle line during the 1880s. These removable terminal tuning “cooks” or “bits” of tubing were added to the bugle between the mouthpiece and the bugle. These devices lengthened the bugle in order to lower its pitch. It’s important to note that this was by no means a novelty to brass instruments, but it would appear that the manner in which the tuning crooks were applied by Swift specifically to the bugle ensemble was new to North America.

Swift’s bugles were pitched in “B-flat.” By adding tuning crooks to select instruments of the bugle choir, he was able to lower the pitch of these instruments to “F.” Both keys of bugles were very familiar to military buglers, but they were seldom used simultaneously in an ensemble. The incorporation of both “B-Flat” and “F” bugles permitted the bugle band to perform a wider variety of music.

With the addition of snare drums to the percussion section, the Queen’s Own Bugles performed numerous exhibitions in Canada and the United States during the late 1880s. It is unknown to what extent this ensembles impacted the “trumpet and drum bands” of the United States during this period. There is evidence of corps utilizing tuning cooks in the United States for their “G” bugles well into the 1930s.(61)

|

|

|

|

Queens Own Bugle Band, a Canadian military bugle band associated with Queens Own Rifles taken in Niagra, Ontario during World War II (1939-1945). Photo from collection of Doug Hester, a bugler wounded at the Normandy Invasion in 1944. |

Throughout the bugle band’s history, members have served bravely as battlefield buglers and infantry soldiers in numerous wars and conflicts. All the while the band continued to maintain its high performance standards and competitiveness.

The ensemble’s instrumentation remained virtually unchanged until piston bugles in “B-Flat” were reluctantly introduced to the Queen’s Own in 1947, as well as melodic percussion.

Trumpet and Drum Corps

During the later part of the nineteenth century, bugles of several varieties could be purchased from virtually every mail order musical instrument manufacturer. During the 1870s and 1880s, these bugles were paired with marching percussion in the U.S. The combination of the two became popular among the military forces. Often, these “trumpet and drum corps” would parade behind regimental brass bands during parades to play alternately during the march.(62)

During 1886, John Phillip Sousa noticed the increasing popularity of the trumpet

|

|

|

|

John Philip Sousa's first book Trumpet and Drum written in 1886 included original compositions and instruction materials for trumpet and drum corps. |

and drum corps in Washington, D.C. and wrote a book in hopes of developing their precision. Trumpet and Drum was Sousa’s first book and included basic music theory, technical exercises for the trumpet and percussion, standard bugle calls, and eight original compositions prepared expressly for the trumpet and drum corps.

It’s important to note that American straight (or valve-less) bugles have been historically referred to as “trumpets” because of their cylindrical (as opposed to conical) design. Depending on the geographical location, the term “trumpet” and “bugle” are often synonymous.

The year 1886 also marked the first year of Purdue’s collegiate trumpet and drum corps. Years later, this ensemble (and many other trumpet and drum corps) would evolve into marching bands.

Bugles for Every Need

|

|

|

|

|

High wheel cyclist reprinted from www.thewheelmen.com |

The late 1800s provided an astonishing assortment of bugles offered by manufacturers. Bugles for the military were offered in several keys and several configurations. Likewise, bugles designed for civilian use were also becoming more prominent.

One of the most unique incarnations of the bugle were produced for bicycle enthusiasts. As the “high wheel” bicycle became more commonplace in the 1870s and 1880s, there was a great deal of enthusiasm surrounding it. Predating the automobile, bicycles offered Americans a new sense of cost-effective mobility and freedom. Enthusiasts formed clubs and began to compete with other bicycle clubs in riding competitions. Bugles were likely first used with bicycles to provide a method of warning to pedestrians, but soon the bugles were used to issue commands to riding clubs during competitions.

|

|

|

Brass bicycle bugle signed “The Bicycle Bugle New Model 3 turns Henry Keat & Sons Matthias Ra. Stroke Newington London” (8 inches long). From Copake Auction, Inc. |

A specialized bugle was created for use by bicyclists. Triple coiled, these compact bugles were small, but were the same length as larger double-coil bugles. The compact design of the bicycle bugle was also utilized for pocket bugles. Bicycle bugles sometimes utilized an oval bell flare instead of the traditional round configuration.(63)

Becoming a symbol for the bicycle competitions, some finely crafted presentation bicycle bugles were used as prized for some of the more prestigious bicycle competitions. These particular bugles are considered highly-prized and valuable by today’s instrument collectors.

It’s unclear what affect these instruments had on the design of the small horns with rubber bellows that were later used on bicycles and early automobiles. To this day, the universal bugle symbol is used as identification on horn buttons found on automobile steering wheels.

Standardization of the “G” Bugle

Standardization of the “G” bugle occurred during the early 1890s when the U.S. Army decided to change from the then current standard of the “F” trumpet (with or without a “C” crook). Eventually, new designs began to appear and the 1892 pattern “G” trumpet with slide and “F” crook for use by cavalry was approved, along with the 1894 pattern “B-Flat” trumpet for infantry. Officer’s bugles from this period resembled British duty bugles and were pitched in “C.” Artillery bugles from this period were pitched in “G.”

|

| An image of the M1892 pattern field trumpet from the U.S. Army Quartermaster's specification dated May 2, 1892. The small crook pictured below the instrument could be inserted between the mouthpiece and the trumpet to lower the instrument's pitch to F. |

The 1892 pattern “G” trumpet would eventually supplant all others and become the regulation for all services. This standardization is also responsible for the American Legion’s adoption of the “G” trumpet for drum and bugle corps that began to form during the late 1920s.

Commentary has occurred theorizing that twentieth century drum corps utilized “G” bugles because of some perceived acoustical advantage over other pitched instruments. Ironically (but not surprisingly), North American drum corps would utilize “G” bugles for most of the twentieth century simply because of a nineteenth century bureaucratic edict.

Click here for part three

Endnotes

(23) Jack Carter, letter to author, 21 Feb 1996.

(24) Allan J. Ferguson, "Trumpets, Bugles and Horns in North America: 1750-1815," Military Historian and Collector (Vol. XXXVI, Spring 1984) 2.

(25) Ferguson 3.

(26) Raoul F. Camus, Military Music of the American Revolution (Chapel Hill, NC: The U of NC Press, 1976) 65.

(27) Camus 73.

(28) George C. Neumann, Collector's Illustrated Encylopedia of the American Revolution, (Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1975) 194.

(29) Library of Congress, Journals of the Continental Congress 1774-1789 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1908) 539-541.

(30) Jack Carter, letter to the author, 02 Jan 1996.

(31) Jack Carter, letter to the author, 02 Jan 1996.

(32) Riehn 13.

(33) Randy Rach, Tune Ancestry of Modern U.S. Army Bugle Calls (March 25, 1996) 4.

(33a) Bob Frankling, email to author, 16 Dec 2009

(34) Ferguson 5.

(35) Ferguson 5.

(36) Ferguson 5.

(37) Ferguson 5.

(38) Ferguson 5.

(39) William Carter White, A History of Military Music in America (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1944) 50.

(40) White 58.

(41) White 58.

(42) J.J. Donnelly, Martial Album for Modern Fife, Bugle and Drum Corps (New York: Carl Fischer, Inc.)

(43) Randall Rach, letter to author, 24 Dec 1995.

(44) Robert and Margaret H. Hazen, The Music Men: An Illustrated History of Brass Bands in America, 1800-1920 (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987) 17.

(45) Hazen, 111.

(46) Henry George Farmer, "Handel's Kettledrums" and Other Papers on Military Music, (2nd Edition 1960) 75.

(47) Farmer 75.

(48) Farmer 75.

(49) William Waterhouse, The New Langwill Index, A Dictionary of Musical Wind-Instrument Makers and Inventors, (London, Tony Bingham, 1993) 90.

(50) Renato Meucci, "The Pelitti Firm: Makers of Brass Instruments in Nineteenth-Century Milan," Historic Brass Journal, Volume 6, 1994: 312.

(51) Meucci 312.

(52) Meucci 319.

(53) Sadie 222.

(54) The History of the First World War, (New York: Grolier Inc., 1965) 366.

(55) Hazen 135.

(56) Jack T. Carter, letter to author, 29 Feb 1996.

(57) U.S. Marine Corps, Manual for Field Musics, (Washington, D.C., 1935) 2.

(58) U.S. Marine Corps 2, 3.

(59) Jack T. Carter, letter to author, 23 Jan 1996.

(60) Lt. Col. W.T. Bernard, The Queen's Own Rifles of Canada 1860-1960, (Ontario) 369.

(61) Nick Michielli, Letter to the Editor, Drum Corps News, 14 Jan 1976.

(62) Jack Carter, letter to author, 02 Dec 1995.

(63) Jack Carter, letter to author, 21 Feb 1996.

Home | Articles | Search | Enroll | Equipment | Staff | Souvies | Links | Updates